Abate 2013 Modular Package Manager

Updated on 12/10/2022 🗒️ Edit on GitHubA Modular Package Manager Architecture

TLDR

Mancoosi Package Manager (MPM) is a hodge podge of debian tools (the client, and hooks to apt) in Python and standards (using CUDF as input output for an upgrade scenario) and it’s slow as heck, but performs better than other Debian-based package mangers. This paper is more a review of CUDF and then argument that modularity is the way to go, as demonstrated by a few studies that show this strategy comes up with more optimal solutions.

Overview

The authors present package managers the tools to install/remote software, and argue that a modular architecture is ideal to allow for choosing backends and dependency solvers. Installing packages is hard because:

- you can’t easily put them together, they are modular

- you can’t easily install more than one version of the same thing

- they can change rapidly, and an initial install of several packages can break in the future (conflits)

- you have to often install them on shared resources with different levels of permissions, etc.

Because installing packages is hard, we have package managers! Package managers generally:

- they are the tools that the user interacts with (e.g., “apt-get install…)

- can get and install packages from some remote resource (e.g., mirrors, cloudy places, GitHub)

- they have some means to assess dependencies and create an update plan (e.g., that CUDF text file)

- they execute the update plan, and fall back if things fail.

This can get complicated very quickly because of logical complexity (if you have a huge set of dependencies and conflicts it’s harder to find a solution) and scale (the more packages, the bigger the hairball to untangle). Scale also takes into account the size of “the place you install packages from.” The more you have, the more resources that are needed for the remote, period.

The authors argue that the front end (the client interacting with the user) should be separate from the back end (the dependency solver). They present their proof of concept, the Mancoosi Package Manager (MPM) that uses the Common Upgradeability Description Format (CUDF) and something called “the user preferences language” that helps do just that - get preferences from the user.

The Upgrade Problem

You are usually okay when starting with a FOSS operating system, but as soon as a few packages upgrade, you start running into dependency problems. This leads us to… dependency hell!

the user gets entangled in an inextricable web of dependencies and conflicts that state-of-the-art package managers are unable to handle.

And I love that this definition is included in the paper! They next walk through a dummy example of how things break with python-simpy, showing the packages updated, installed, and removed for each (see [1]). They show how MPM is better because it gives the user control to specify criteria. For example:

mpm -c "-removed,-changed" install python-simpy

Says to install python-simply and minimize removed and changed packages. The command is slow (~10 seconds) and they justify this by saying it’s just a proof of concept. This gives us a good idea for a framework to test package managers.

infoWe would want to be able to build contains across package managers (apt-get, yum, aptitude, etc.) and then simply install a particular package, and parse the terminal output to see the decision that was decided upon.

See the containers idea section for this idea.

Modular package management

The authors say that dependency solving is really hard, and it makes sense to de-couple it from the rest of the package manager (the client to manage software components) so that they can be re-usable components. This brings back the idea of “solver farms,” or externally hosted solvers. Figure 1 in their paper shows “modular package manager architecture” but I didn’t find it very intuitive.

Scenarios

This is the first paper that I’ve encountered that describes different scenarios that package managers can run into (e.g., healthy, peaceful). This is something that I think should be better flushed out into an idea - “What is the standard or schema for some package manager flow?” See the flow page for this idea. It sounds like there is work in progress to standardized criteria and aggregation functions, but this paper was 7 years ago, so we will need to read a more recent one (abate 2020?) to know the current status.

Solvers

This paper has a short list of solvers (p. 16) that use CUDF, but I remember a more robust table in the Abate 2020 paper, so I won’t reproduce the list here.

Takeaways

The takeaway from this paper is that many package managers use ad-hoc heuristics, and this is messy. If we uncouple dependency resolution from the package manager (e.g., the solvers) we can more easily share components. The package manager should act as a skeleton client to interact with the user, and we should be able to plug in components. This paper presents the general idea of embracing already existing package managers (e.g., apt) and functionality, and integrating into a new tool (MPM) that can take as input criteria and solvers, and then use CUDF as an input/output format to make them more modular. I think this was probably a novel idea back in 2013, but now there must be more recent work that improves upon the ideas.

Terms

- package A software component paired with metadata that describes how to install it on a system. Each package can follow a unique development pipeline and even versioning scheme reference.

- CUDF The Common Upgradeability Description Format, a text file that describes all conflicts, and dependencies based on some user preferences to install software. See the [cudf] term page for notes from this paper.

- user preference language Allows to specify a list of criteria (sometimes called measurements) of package selectors, and each has a plus or minus prefix to indicate minimizing or maximizing.

Mancoosi Package Manager (MPM)

This is a proof of concept implementation of the idea of the authors, a modular package manager. It uses CUDF to capture dependency information and the user preference langauage to ask the user for what to optimize, etc. The implication is that the MPM is a creation of the Mancoosi project. The idea of MPM is that it uses CUDF as input/output. MPM:

- uses apt on the back end to parse the command line and install packages

- has removed, new, changed, and notuptodate as criteria

- you can specify a solver plugin with

-s <solver>(that’t kind of cool! Will we try this with a custom solver?) - you can specify a criterion with

-c <option>(e.g., -removed) -o <option>passes an option to aptdebtodudfis used to translate Debian package metadata to CUDF- MPM is written in Python and uses Python bindings to apt (wow, didn’t expect that!)

- supports all the same command line arguments as apt

- uses the

aspcudsolver that won one of the MISC competitions.

infoRegardless of the format we use to represent an upgrade scenario (e.g., CUDF) there would always need to be some kind of translator to derive it from the original user request and package manager.

The above has me wondering if we want to just work on the solver (e.g., take the same constraints but add another level of information to it) or if we want to require the CUDF specification to better represent some of this information (arguably this would be harder because the package managers would have to extract it, and might be redundant if we would need to double check again). I’m also wondering why there is such a focus on apt/Debian.

Performance Testing

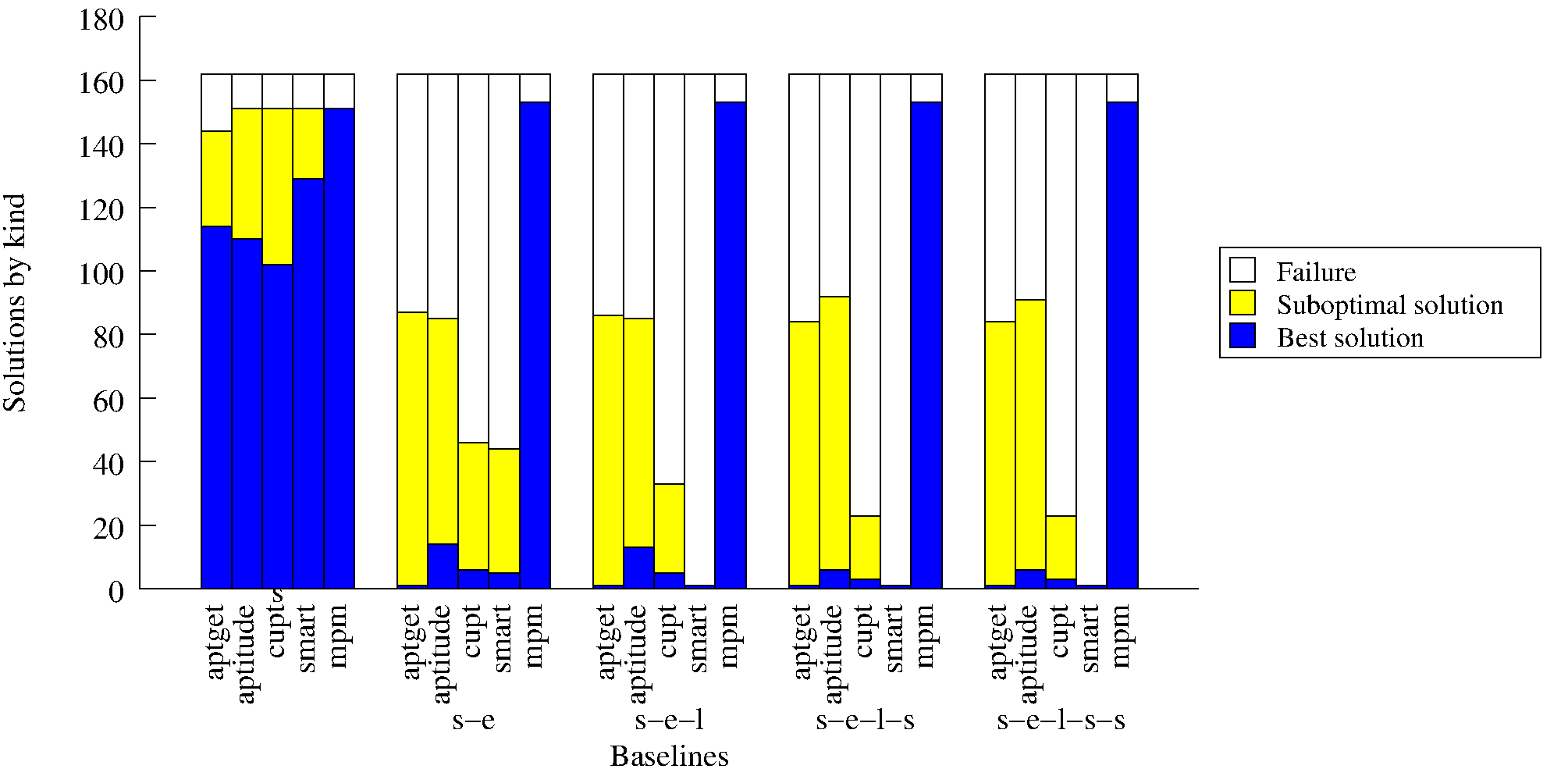

The authors first justify that time isn’t important because their implementation is a proof of concept. For testing they use containers, and do 5 groups of tests that add/remove the same package under different Debian releases. The salient difference in the package release universes is that newer ones have many more packages (logically). For each, they did 162 (why 162?) install/remove requests, and randomly selected packages ensuring that there is a solution (again, how?) They only consider results that made it within the 300s timeout. They classified results into three categories:

- best solution

- optimal solution

- failure (crashed or not a correct solution)

They show that performance varies between 50% and 75%, with MPM being the best (see figure).

This is overall one way to go about testing how well solvers work between different package managers, but it seems rough around the edges because they are working as black boxes for the most part.

Related Work

Pages 20-21 walk through Debian and RHEL distribution package managers (apt vs. yum) and all the associated tools that do everything from fetch packages to using solvers. The interesting observation here is that tools are optimized to their repository sets, e.g., a well defined set of repository metadata can allow for a heuristic that ensures some solution. Table 2 is useful (and small enough to include here)

| Tool | Solver | Optimization | Complete |

|---|---|---|---|

| apt-get | internal | hard-coded | no |

| aptitude | internal | hard-coded | no |

| cupt | internal | hard-coded | no |

| smart | internal | programmable | maybe |

Wow, there are at ton of “hard-coded”s in that table!

Data and Appendix

- Appendix A has a nice summary of the CUDF format

- Data for package install comparison analysis

- Data Writeup with plot.

- P. Abate, R. Di Cosmo, R. Treinen, and S. Zacchiroli, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0950584912001851“A modular package manager architecture”</a> Information and Software Technology, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 459–474, 2013. Full details | PDF